26.11.2011: Unerschütterliche Liebe (Tageszeitung Neues Deutschland):

'via Blog this'

Sunday, 27 November 2011

Saturday, 26 November 2011

Rosa Luxemburgo no Brasil. Hugo E. da Gama Cerqueira

http://meugabinetedecuriosidades.blogspot.com/2011/11/rosa-luxemburgo-no-brasil.html

Rosa Luxemburgo no Brasil

Hugo E. da Gama Cerqueira

|

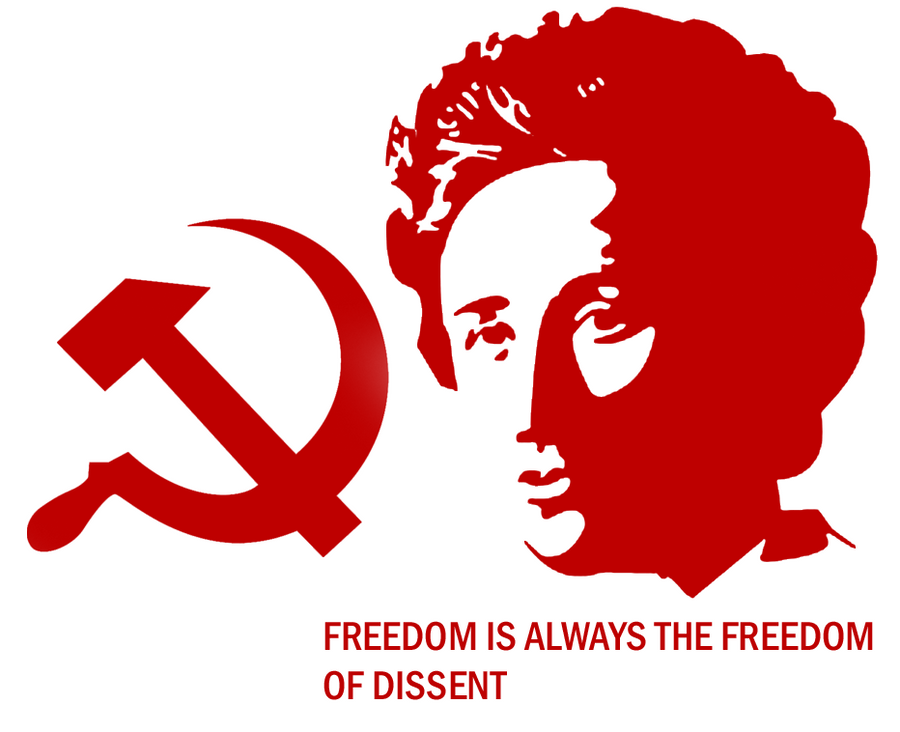

| Rosa: 'Liberdade é sempre a liberdade daquele que pensa de modo diferente'. |

Dias atrás, passeando por uma de minhas livrarias preferidas, deparei com três volumes em capa bege contendo uma coletânea de textos políticos e cartas de Rosa Luxemburgo. Os livros, lançados recentemente pela Editora da Unesp, foram organizados por Isabel Loureiro, que além de ser uma das grandes estudiosas da obra de Rosa, vem cumprindo um papel importante na divulgação de suas ideias no Brasil, dando continuidade ao esforço pioneiro, iniciado no pós-Guerra, pelo grande Mário Pedrosa, e seguido por Paulo Singer, Maurício Tragtenberg, Michael Löwy e outros tantos.

Os volumes contém traduções integrais de muitos textos que, até aqui, ou permaneceram inéditos em português, ou eram conhecidos apenas parcialmente. Além disso, essas traduções foram feitas diretamente dos originais em alemão e polonês.

O volume I cobre o período que vai de 1899 até julho de 1914, início da I Grande Guerra. Começa por "Reforma social ou revolução?", famosa investida crítica ao revisionismo de Bernstein, passando por "Questões de organização da social-democracia russa", de 1904, em que Rosa formula uma crítica aguda à concepção leninista de partido, que culminaria em sua famosa (e profética) crítica ao comportamento autoritário dos bolcheviques no poder, em "A Revolução Russa", que é de 1918.

Este último texto, integra o segundo volume da coletânea. Rosa se insurge ali contra a supressão das liberdades democráticas pelos bolcheviques, liberdades que são essenciais, em sua opinião, para o aprendizado político das massas, para o acúmulo de experiências políticas que é requisito para a afirmação do socialismo. Um socialismo que, logo se vê, não pode ser criado por decreto, mas pela auto-determinação das massas educadas e formadas na experência da liberdade.

É nesse segundo volume que também aparece a famosa "brochura de Junius", como é conhecido o texto "A crise da social-democracia", escrito na prisão e publicado em 1916, na Suíça, sob o pseudônimo de Junius. É nele, ao fazer a crítica à social-democracia alemã por sua adesão à guerra, que Rosa nos apresenta a fórmula "socialismo ou barbárie" para expressar o dilema que caracterizaria aquele momento:

"Hoje encontramo-nos, extatamente como Friedrich Engels previu há uma geração, 40 anos atrás, perante a escolha: ou o triunfo do imperialismo e decadência de toda a civilização, como na antiga Roma, despovoamento, desolação, degeneração, um grande cemintério; ou vitória do socialismo, isto é, da ação combativa consciente do proletariado internacional contra o imperialismo e seu método, a guerra. Esse é um dilema da história mundial, uma coisa ou outra, uma balança cujos pratos oscilam e tremem perante a decisão do proletariado com consciência de classe" (p. 29).Ainda que se possa discutir o significado preciso da expressão "barbárie" nessa fórmula, o fato é que, como Löwy apontou num dos capítulos de seu Método dialético e teoria política, ela nos coloca diante de uma concepção de história nova, anti-determinista, em que o curso dos acontecimentos não pode ser estabelecido previamente com base em "leis objetivas" mas, ao contrário, a subjetividade joga um papel decisivo na determinação dos rumos que serão seguidos. História como processo aberto, sujeita ao progresso que, entretanto, não é inevitável.

Finalmente, o terceiro volume traz uma seleção das "mais de 2.700 cartas, cartões-postais e telegramas de Rosa Luxemburgo" que constam da edição alemã de suas Gesammelte Briefe, pela Dietz. Escritora compulsiva, as cartas de Rosa permitem entrever sua personalidade, seus interesses, não apenas intelectuais, mas também suas paixões, alegrias e dores. Nesta versão, elas estão divididas entre cartas escritas no período anterior à declaração da I Guerra, que incluem sua amorosa e tumultuada correpondência com Leo Jogiches, e as cartas do período da Guerra, durante o qual Rosa permaneceu encarcerada.

Com o lançamento desses três volumes, reunindo uma coleção abrangente de textos em tradução e edição bem cuidadas, os brasileiros podem se orgulhar de comemorar à altura e com muito estilo os 140 anos dessa figura fascinante que foi Rosa. A professora Isabel Loureiro e sua equipe estão de parabéns pelo trabalho, que irá contribuir imensamente para a difusão das ideias de Rosa Luxemburgo entre os leitores de língua portuguesa. Nada mais oportuno num momento como esse em que vivemos, em que sua reflexão e exemplo ganham tanta atualidade.

— § —

PS. Os volumes dessa coleção podem ser encontrados em diversas livrarias. Aquela que mencionei no início do texto e onde me deparei com eles pela primeira vez é a Canto do Livro, que fica aqui em Belo Horizonte e que eu frequento há um bom tempo. Não se trata de fazer propaganda mas, nestes tempos de livrarias virtuais (que são muito boas), é preciso valorizar quem consegue manter um bom estoque de livros à disposição de leitores incautos.

Monday, 21 November 2011

Tuesday, 15 November 2011

Il VII congresso della IGHM e la presentazione della Festschrift per i 70 anni di Domenico Losurdo

PRESENTAZIONE

Una critica anticonformistica della storia del movimento liberale che chiama in causa i suoi maggiori teorici come gli sviluppi e le scelte politiche concrete delle società e degli Stati che ad essi si richiamano; un grande affresco comparatistico, nel quale il confronto serrato tra il liberalismo, la corrente conservatrice e quella rivoluzionaria, svolto lungo diversi secoli, fa saltare gli steccati della tradizione storiografica e disvela il faticoso percorso di costruzione della democrazia moderna; l’abbozzo di una teoria generale del conflitto che muove dalla comprensione filosofica, in chiave dialettica, del rapporto tra istanze universalistiche e particolarismo; ancora, un’applicazione del metodo storico-materialistico che mira ad un suo radicale rinnovamento attraverso la rivendicazione dell’equilibrio tra riconoscimento e critica della modernità e che si concretizza in una originale ontologia dell’essere sociale.

Sono queste le linee-guida del percorso di ricerca di Domenico Losurdo, un percorso che è iniziato negli anni Settanta e che - innovando la tradizione di una scuola che si richiama ad Arturo Massolo e poi a Pasquale Salvucci e Livio Sichirollo - si è concretizzato sinora in quasi 250 titoli. Per festeggiare i suoi 70 anni, che cadono il 14 novembre, la Internationale Gesellschaft Hegel-Marx für dialektisches Denken, la Facoltà di Scienze della Formazione e il Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Uomo dell’Università di Urbino hanno chiesto agli amici e colleghi di Domenico Losurdo di contribuire a questa Festschrift.

Ringraziamo l’Istituto Italiano per gli Studi filosofici, con il suo presidente Gerardo Marotta e il suo segretario Antonio Gargano, per avere sollecitato e sostenuto la nostra iniziativa. Ringraziamo La scuola di Pitagora Editrice per aver pubblicato questa raccolta e l’Università di Urbino, con il Rettore Stefano Pivato, per averla finanziata. Ringrazia-mo infine gli autori che hanno voluto contribuirvi, scusandoci per non aver potuto accogliere tutte le adesioni.

La Festschrift viene presentata in occasione del Congresso della Internationale Gesellschaft Hegel-Marx für dialektisches Denken (Urbino, 18-20 novembre 2011).

Stefano G. Azzarà, Paolo Ercolani, Emanuela Susca

Urbino, ottobre 2011

Partecipano al congresso:

Andre Tosel, Jose Barata-Moura, Vladimiro Giacche, Carlos Nelson Coutinho, Bernard Bourgeois, Tom Rockmore, Joao Quartim Moraes, Bernard Taureck, Ishay Landa, Andreas Wehr, Dogan Gocmen, Graziano Ripanti, Massimo Baldacci, Nicola Panichi, Mario Cingoli, Fabio Frosini, Venanzio Raspa, Antonio De Simone, Paolo Ercolani, Renato Caputo, Giorgio Grimaldi,Stefano G. Azzara, Micaela Latini, Emanuela Susca, Giovanni Semeraro.

Oltre alle relazioni dei partecipanti al congresso, nella Festschrift sono presenti saggi di:

Hans Heinz Holz, Emmanuel Faye, Andras Gedo, Isabel Monal, Jean Robelin,Giuseppe Cacciatore, Tian Shigang, Eduard Gans (Pseudonimo)

Partecipano al congresso:

Andre Tosel, Jose Barata-Moura, Vladimiro Giacche, Carlos Nelson Coutinho, Bernard Bourgeois, Tom Rockmore, Joao Quartim Moraes, Bernard Taureck, Ishay Landa, Andreas Wehr, Dogan Gocmen, Graziano Ripanti, Massimo Baldacci, Nicola Panichi, Mario Cingoli, Fabio Frosini, Venanzio Raspa, Antonio De Simone, Paolo Ercolani, Renato Caputo, Giorgio Grimaldi,Stefano G. Azzara, Micaela Latini, Emanuela Susca, Giovanni Semeraro.

Oltre alle relazioni dei partecipanti al congresso, nella Festschrift sono presenti saggi di:

Hans Heinz Holz, Emmanuel Faye, Andras Gedo, Isabel Monal, Jean Robelin,Giuseppe Cacciatore, Tian Shigang, Eduard Gans (Pseudonimo)

Friday, 11 November 2011

Internationale Gesellschaft Hegel-Marx fuer dialektisches Denken. Universalism, National Question and Conflicts Concerning Hegemony. Proceedings

Gli atti del congresso di Lisbona della Internationale Gesellschaft Hegel Marx

Introduction

by Stefano G. Azzarà

The deep crisis of global capitalism is today developing in a struggle of unprecedented transformation preceded by long historical process not only on the economic but also the political and cultural planes.

The announcement of the “end of history” and of the definitive arrival of a new peaceful world order is representative of a kind of neo-liberalism that emerged at the end of the cold war, but which is contradicted by two decades of war and uninterrupted international tension as well as significant imbalances in every single country. The optimistic declarations of Francis Fukuyama and the bellicose slogan of the clash of civilizations of Samuel P. Huntington and of other neo-conservative American intellectuals characterize this period. This still continues as the inspiration of numerous Western elites searching for a guiding idea to clarify the relations between nations and areas of the world while maintaining an internal consensus in each country. This yields a fundamentalistic and simplified conception of identity as well as instrumentalized conceptions of the enemy, which currently includes Islam, China, and the migratory wave of barbarians from the Third World. This and other slogans have been remarkably effective. They contribute to obscuring the profound disequilibrium in the distribution of wealth, power, rights and opportunities within the industrialized countries while favouring the exportation of the conflict. On the basis of this ideology, the West, and especially the US, identifies with civilization as such and with the very idea of democracy. It seeks to govern in an aggressive way the important transformations now under way in imposing everywhere its own vision of the world and its own priorities. Yet this puts into question the claimed universal validity of the West, which it pretends to export. As Huntington himself admits, “the non-Westerners define what is Western, which the Westerners define as universal.”

What happened? In the second part of the eighteenth century, the ideals of democracy and universal rights of which we became aware through the French Revolution were enriched by the experience of the socialist movement, though still very far from anything resembling a full development, were deeply weakened. Their redefinition in liberalism has blocked these philosophical and political developments both internal and external to the West, critical as well as autocratic, which several decades earlier were understood to be inescapable components of full universalism. In this respect, postmodern philosophy has played a role. Born from the pretext of a radical critique of power and of the state, it is indicative of a destructive anti-dialectical attitude in the confrontation with any form of universalism as such. Its specifically anti-critical exaltation of particular differences remains in a fragile balance between absolute relativism and the apology for stronger systems of law and order.

This gives rise to a form of particularistic and divided universalism tending to negate any acknowledgment in the confrontation with other forms of culture and conscious awareness. Rather than dialogue, it undertakes to realize its superiority with respect to others. But the key to the clash of civilizations is useless to grasp the current situation. It is much more useful to consider these phenomena from a different perspective.

The end of the bipolar world has not only prepared the way for the globalized imposition of capitalist development and occidental values. It has also created the conditions for beginning a more complex process in which the entire world up to the present is inserted as it were within a rigid order. The result is a process of internal development and of uncoupling so to speak in the confrontation between the capitalist economic order as well as the confrontations of the hegemony of American and Western culture. Underneath this conflict between civilizations and development, we must look to history, tradition and religion. There is therefore a more concrete and materialistic struggle with political and geopolitical dimensions which is playing itself out a redefinition of world equilibrium in the twenty first century. The regions which emerged from the colonial period and lay claim to autonomy work in opposition to the neo-colonial project of a Western world looking to confront the crisis of its own authority and not hesitating to appeal to military means. This is a conflict for hegemony, which needs to be characterized. In this conflict, the national question, which has long been thought of as not a contemporary theme in the ideology of globalization, reminds us of its centrality.

The critical instruments and the dialectical means put at our disposal by Hegel and Marx, and in particular their reflections on the relation between universality and particularity, on the nature of the conflict and the role of the intellectual class can help to orient us better in this word and to understand in a more rational manner. This is the task of our meeting, which will take place May 28-30 in Lisbon. It is organized in collaboration with the University of Lisbon, the Department of Human Sciences of the University of Urbino, the Italian Institute of Philosophical Studies, and with the support of Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Fundação Internacional Racionalista and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

The announcement of the “end of history” and of the definitive arrival of a new peaceful world order is representative of a kind of neo-liberalism that emerged at the end of the cold war, but which is contradicted by two decades of war and uninterrupted international tension as well as significant imbalances in every single country. The optimistic declarations of Francis Fukuyama and the bellicose slogan of the clash of civilizations of Samuel P. Huntington and of other neo-conservative American intellectuals characterize this period. This still continues as the inspiration of numerous Western elites searching for a guiding idea to clarify the relations between nations and areas of the world while maintaining an internal consensus in each country. This yields a fundamentalistic and simplified conception of identity as well as instrumentalized conceptions of the enemy, which currently includes Islam, China, and the migratory wave of barbarians from the Third World. This and other slogans have been remarkably effective. They contribute to obscuring the profound disequilibrium in the distribution of wealth, power, rights and opportunities within the industrialized countries while favouring the exportation of the conflict. On the basis of this ideology, the West, and especially the US, identifies with civilization as such and with the very idea of democracy. It seeks to govern in an aggressive way the important transformations now under way in imposing everywhere its own vision of the world and its own priorities. Yet this puts into question the claimed universal validity of the West, which it pretends to export. As Huntington himself admits, “the non-Westerners define what is Western, which the Westerners define as universal.”

What happened? In the second part of the eighteenth century, the ideals of democracy and universal rights of which we became aware through the French Revolution were enriched by the experience of the socialist movement, though still very far from anything resembling a full development, were deeply weakened. Their redefinition in liberalism has blocked these philosophical and political developments both internal and external to the West, critical as well as autocratic, which several decades earlier were understood to be inescapable components of full universalism. In this respect, postmodern philosophy has played a role. Born from the pretext of a radical critique of power and of the state, it is indicative of a destructive anti-dialectical attitude in the confrontation with any form of universalism as such. Its specifically anti-critical exaltation of particular differences remains in a fragile balance between absolute relativism and the apology for stronger systems of law and order.

This gives rise to a form of particularistic and divided universalism tending to negate any acknowledgment in the confrontation with other forms of culture and conscious awareness. Rather than dialogue, it undertakes to realize its superiority with respect to others. But the key to the clash of civilizations is useless to grasp the current situation. It is much more useful to consider these phenomena from a different perspective.

The end of the bipolar world has not only prepared the way for the globalized imposition of capitalist development and occidental values. It has also created the conditions for beginning a more complex process in which the entire world up to the present is inserted as it were within a rigid order. The result is a process of internal development and of uncoupling so to speak in the confrontation between the capitalist economic order as well as the confrontations of the hegemony of American and Western culture. Underneath this conflict between civilizations and development, we must look to history, tradition and religion. There is therefore a more concrete and materialistic struggle with political and geopolitical dimensions which is playing itself out a redefinition of world equilibrium in the twenty first century. The regions which emerged from the colonial period and lay claim to autonomy work in opposition to the neo-colonial project of a Western world looking to confront the crisis of its own authority and not hesitating to appeal to military means. This is a conflict for hegemony, which needs to be characterized. In this conflict, the national question, which has long been thought of as not a contemporary theme in the ideology of globalization, reminds us of its centrality.

The critical instruments and the dialectical means put at our disposal by Hegel and Marx, and in particular their reflections on the relation between universality and particularity, on the nature of the conflict and the role of the intellectual class can help to orient us better in this word and to understand in a more rational manner. This is the task of our meeting, which will take place May 28-30 in Lisbon. It is organized in collaboration with the University of Lisbon, the Department of Human Sciences of the University of Urbino, the Italian Institute of Philosophical Studies, and with the support of Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Fundação Internacional Racionalista and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

Eduardo Chitas (University of Lisbon)

Manfred Buhr, ou d’une loyauté sans frontières en philosophie

I. Plenar y conf erenc es

Domenico Losurdo (University of Urbino)

La rivoluzione, la nazione e la pace

Bernard Bourgeois (University of Paris I - Pantheon-Sorbonne)

L’identité nationale: devoir de mémoire et devoir d’oubli

Jean Robelin (University of Nice)

Universel, exclusion, interculturalité

Tom Rockmore (Duquesne University)

Social Contradiction, Globalization and 9/11

Bernhard Taureck (University of Braunschweig)

Nos trois absences: l’universel, la croissance économique, la démocratie

Nicola Panichi (University of Urbino)

Il «peso delle ombre». Universalismo e universalità nel Rinascimento

Roberto Finelli (University of Rome III)

“Abstraction” contre “différence” et “contradiction”.

Une hypothèse interprétative de la post-modernité

Jose Barata-Moura (University of Lisbon)

Que faire? Sur le travail de l’universel

6

II. Ateli ers

Atelier 1

Irene Viparelli (University of Salerno)

Il 1848. L’oggetto della teoria marxiana?

Renato Caputo (High School “Benedetto da Norcia”, Rome)

Universalismo e questione nazionale nell’elaborazione

del sistema hegeliano a Jena

Emanuela Susca (University of Urbino)

Universalismo e questione nazionale nel pensiero di Pierre Bourdieu

Joao Aguiar (University of Porto)

Does culture have something to do with class domination?

The aestheticization of everyday life and the political

and symbolic retraction of Western’s working classes

Atelier 2

Adele Patriarchi (High School “Primo Levi”, Rome)

Tra le due comunità: la filosofia del lavoro davanti alla flexicurity

Raffaella Santi (University of Urbino)

Esiste una storia della filosofia irlandese? Il nazionalismo culturale

in Irlanda e la sua recente ridefinizione

Jose Neves (University of Lisbon)

Nem a vossa liberdade, nem a vossa protecção? Notas de leitura

de «Crítica de List» e de «Discurso sobre a questão do comércio livre»

Barbara Pistilli (University of Urbino)

Tra ragione e passioni: la persona come orizzonte critico in Baltasar Gracián

Atelier 3

Patricia Ponte Bastos (University of Lisbon)

Individuo e Sociedade: a dialéctica de uma relação

7

Silverio da Rocha-Cunha, Joao Tavares Roberto (University of Evora)

La Mega-machine de l’Universalisme: de la simplification moderne

jusqu’à l’alternative de Serge Latouche

Mafalda Blanc (University of Lisbon)

Etre Rationalité et Idée

Marco Sgattoni (University of Urbino)

Pretese universalistiche e opposizione scettica nell’autunno del Rinascimento

Atelier 4

Luis Moita (Free University of Lisbon)

Espaços económicos e configurações políticas

Roberto Fineschi (Italian School for Liberal Arts and AHA

– University of Oregon)

Marx after philology

Pedro Santos Maia (Cacilhas High School,Tejo)

Notre temps: notes sur le capitalisme, l’écologisme et l’universalisme

Mario Cingoli (University of Milan-Bicocca)

La Scienza della logica come romanzo del pensiero.

Destinazione, costituzione e limite

Atelier 5

Luka Bogdanic (University of Zagreb)

L’autodeterminazione nazionale in Lenin alla luce

della Prima guerra mondiale

Mariafilomena Anzalone (Institut for Human Sciences, Florence)

L’universalismo etico di K.-O. Apel tra dialogo e conflitto

Leonardo Pegoraro (University of Urbino)

Vittime di riserva. Le sterilizzazioni coatte degli indiani d’America

Stefano G. Azzara (University of Urbino)

Arthur Moeller van den Bruck: liberalismo, conservatorismo

e Rivoluzione conservatrice

INDEX

Friday, 4 November 2011

Primo incontro del Controcorso sulla crisi a cura del Collettivo di Fisica e di AteneinRivolta Roma on Vimeo

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Dominio senza direzione? Egemonia reale e guerra nel capitalismo crepuscolare

Pubblico online la relazione acclusa negli atti del forum della Rete dei comunisti dal titolo "Il giardino e la giungla" del 18-19...

-

Papa, papi e dottrina sociale della chiesa di Roberto Fineschi L’elezione di un nuovo papa suscita inevitabilmente grande interesse per il...

-

The Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) Project ...

-

Scuola amore mio. Crepuscoli programmati di Roberto Fineschi 1) “Classi” e scuole nel capitalismo crepuscolare A che cosa serve la scuola in...